Apostolic Era (0-100 AD)

The Apostolic Era began with Jesus’ Crucifixion, Resurrection, and Ascension, followed by Pentecost and the establishment of the Jerusalem Church. Key events include the martyrdom of Stephen, the missionary journeys of Paul, and the spread of Christianity among Jews and Gentiles.

- Crucifixion, Resurrection, and Ascension of Jesus.

- Descent of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost.

- Foundation of the Jerusalem Church by the Apostles.

- Persecution of early Christians and the stoning of Stephen.

- Paul’s conversion and missionary journeys.

This period laid the foundation for the spread of Christianity beyond Jerusalem.

1.1 Crucifixion, Resurrection, and Ascension of Jesus

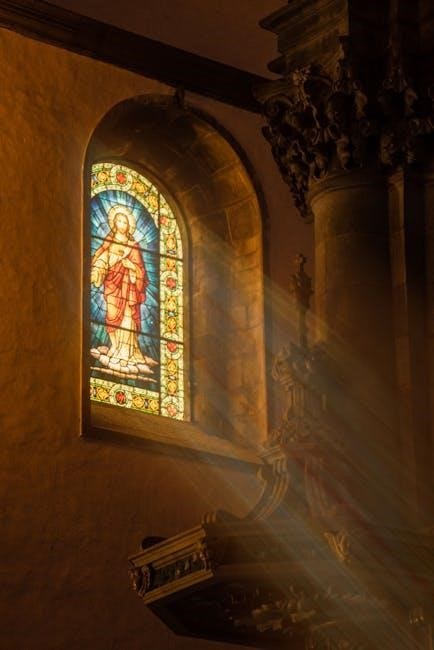

The Crucifixion of Jesus, followed by His Resurrection and Ascension, marks the foundational events of Christianity. Jesus was crucified under Pontius Pilate, a pivotal moment seen as a sacrifice for humanity’s sins. His Resurrection on the third day is central to Christian faith, confirming His divine nature. The Ascension, 40 days later, saw Jesus ascend to heaven, concluding His earthly ministry. These events, recorded in the Gospels, became the cornerstone of Christian theology, emphasizing salvation through Jesus’ sacrifice and triumph over death. The Resurrection and Ascension inspired the Apostles to spread His teachings, launching the Christian movement.

- Crucifixion under Pontius Pilate.

- Resurrection on the third day.

- Ascension into heaven 40 days later.

- Foundation of Christian theology and mission.

1.2 The Great Commission and the spread of Christianity by the Apostles

After Jesus’ Ascension, the Apostles, empowered by the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, fulfilled the Great Commission to spread His teachings worldwide. Peter preached to Jews and Gentiles, while Paul, a former persecutor, became a prominent missionary, establishing churches across Asia Minor, Greece, and Rome. Their journeys, despite persecution, laid the foundation for the early Christian Church, uniting diverse cultures under one faith. This period saw the transformation of a local Jewish sect into a global movement, shaping the future of Christianity.

- Pentecost and the empowerment of the Apostles.

- Peter’s ministry to Jews and early Gentile converts.

- Paul’s missionary journeys and epistles.

- Establishment of churches in the Mediterranean world.

Early Christianity (100-500 AD)

Early Christianity faced persecution under Roman emperors but flourished, spreading across the Mediterranean. Key events include the Edict of Milan, which legalized Christianity, and major theological councils.

- Persecution under Roman emperors like Nero and Diocletian.

- Legalization of Christianity through the Edict of Milan (313 AD).

- Major theological councils like Nicaea and Constantinople.

2.1 Persecution under Roman Emperors

During the early Christian era, Roman emperors often viewed Christianity as a threat, leading to widespread persecution. Emperor Nero famously blamed Christians for the Great Fire of Rome in 64 AD, resulting in brutal executions. Similarly, Emperor Diocletian’s reign (284-305 AD) saw one of the most severe persecutions, aiming to eradicate Christianity. Christians were forced to renounce their faith, and those who refused faced torture, imprisonment, or death. Despite these hardships, the faith persisted, and martyrdom became a powerful symbol of devotion. This period strengthened the resolve of early Christians and set the stage for the eventual acceptance of Christianity within the Roman Empire.

- Nero’s persecution and the execution of Saints Peter and Paul;

- Diocletian’s “Great Persecution” targeting Christians.

- Martyrdom as a defining feature of early Christian identity.

2.2 The Edict of Milan and the rise of Constantine

In 313 AD, Emperor Constantine issued the Edict of Milan, granting religious tolerance to Christians within the Roman Empire. This marked a pivotal shift, ending decades of persecution and allowing Christianity to flourish. Constantine’s personal conversion after his victory at the Battle of Milvian Bridge in 312 AD was instrumental in this change. The Edict not only legalized Christianity but also restored confiscated properties to the Church. Constantine’s reign saw the construction of major Christian sites, such as the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. His support laid the groundwork for Christianity’s rise as a dominant force in the empire, culminating in its official adoption under subsequent rulers.

- Constantine’s vision before the Battle of Milvian Bridge.

- Legalization of Christianity through the Edict of Milan.

- Restoration of Church properties and promotion of Christian sites.

2.3 The Councils of Nicaea, Constantinople, Ephesus, and Chalcedon

These councils were pivotal in shaping Christian doctrine. The Council of Nicaea (325 AD) addressed Arianism, affirming Jesus’ divinity and establishing the Nicene Creed. Constantinople (381 AD) confirmed the Trinity and rejected Macedonianism. Ephesus (431 AD) condemned Nestorianism, declaring Mary as Theotokos (God-bearer). Chalcedon (451 AD) defined Christ’s dual nature, uniting orthodox Christianity. These councils resolved theological disputes, solidified doctrine, and fostered unity, leaving a lasting legacy in Christian theology.

- Nicaea (325 AD): Affirmed Jesus’ divinity and the Trinity.

- Constantinople (381 AD): Reaffirmed the Trinity and rejected Macedonianism.

- Ephesus (431 AD): Condemned Nestorianism and declared Mary Theotokos.

- Chalcedon (451 AD): Defined Christ’s two natures, human and divine.

Medieval Christianity (500-1500 AD)

Medieval Christianity saw the rise of the Papacy, monasticism, and the preservation of Christian knowledge. The Church influenced society, art, and politics, shaping Europe’s identity during this period.

- The fall of the Western Roman Empire and the Church’s growing authority.

- Monastic movements and the spread of Christian education.

- The Crusades and their impact on Christian-Muslim relations.

- The Black Death’s influence on religious practices and societal change.

This era was marked by both spiritual growth and significant challenges, leaving a lasting legacy on Christianity.

3.1 The fall of the Western Roman Empire and the rise of the Papacy

The Western Roman Empire’s collapse in 476 AD marked a pivotal shift in Christian history. As political stability crumbled, the Catholic Church emerged as a unifying force, filling the power vacuum. The Papacy, led by figures like Pope Gregory I, gained authority, asserting spiritual and temporal leadership. The Church preserved classical knowledge and maintained social order, becoming central to medieval life. This period saw the rise of monasticism and the consolidation of Church power, laying the groundwork for the Papacy’s dominance in Europe during the Middle Ages.

- The collapse of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD.

- The Church’s role in maintaining order and preserving knowledge.

- The rise of the Papacy as a central authority.

This era solidified the Church’s influence, shaping the medieval Christian world.

3.2 The Black Death and its impact on the Church

The Black Death (1346–1353) devastated Europe, causing unprecedented social, economic, and religious upheaval. The Church faced criticism for its inability to stop the plague, leading to widespread disillusionment. Many questioned the clergy’s moral authority, while flagellant movements emerged, blending piety with public penance. The crisis reduced the Church’s wealth and influence, as survivors challenged traditional hierarchies. Some turned to mysticism or heretical movements, further eroding Church control. The plague accelerated existing reforms and set the stage for future theological debates, reshaping the medieval Church’s role in society.

- The Church’s failure to halt the plague led to public distrust.

- Flagellant movements and mysticism gained prominence.

- Decline in Church wealth and societal influence.

3.3 The Crusades and their influence on Christian-Muslim relations

The Crusades (11th–13th centuries) were a series of military campaigns initiated by the Catholic Church to reclaim the Holy Land from Muslim rule. These conflicts led to widespread violence, including the Siege of Jerusalem in 1099, where thousands of Muslims and Jews were massacred. The Crusades deeply strained Christian-Muslim relations, fostering mistrust and hostility that persists to this day. They also highlighted religious and cultural divisions, solidifying perceptions of Islam as a threat to Christianity. The Fourth Crusade further complicated relations by targeting Christian communities, such as the sack of Constantinople in 1204. These events left a lasting legacy of tension and shaped interfaith dynamics for centuries.

- The Crusades were driven by religious and political motives.

- Violence against Muslim and Jewish populations intensified animosity.

- The conflicts reinforced stereotypes and prolonged religious divisions.

Reformation and Counter-Reformation (1500-1700 AD)

The Reformation, led by Martin Luther and John Calvin, challenged Catholic doctrine, sparking Protestantism. The Counter-Reformation saw the Catholic Church reaffirm its teachings and practices, shaping modern Christianity.

4.1 The Protestant Reformation led by Martin Luther and John Calvin

The Protestant Reformation, initiated by Martin Luther in 1517, challenged Catholic Church practices like indulgences, sparking widespread change. Luther’s 95 Theses criticized Church corruption, emphasizing salvation through faith alone. John Calvin furthered Reformation ideals, advocating predestination and a disciplined Christian life. Their teachings spread rapidly, leading to the emergence of Protestant denominations. The Reformation emphasized biblical authority and individual faith, reshaping Christianity and causing a significant split from the Catholic Church. This period marked a pivotal shift in religious thought, influencing both theology and culture across Europe.

4.2 The Council of Trent and the Catholic Church’s response

The Council of Trent (1545–1563) was the Catholic Church’s response to the Protestant Reformation, aiming to reform internal practices and counter Protestant doctrines. It reaffirmed traditional teachings on sacraments, priestly authority, and indulgences, while addressing abuses like nepotism and simony. The Council emphasized the authority of both Scripture and Tradition, rejected sola fide, and promoted the use of religious art and devotions. Trent also led to the establishment of seminaries to improve priestly education and the formation of a more unified Catholic identity. This period marked a significant effort by the Church to revitalize itself and counter Protestant influence, shaping the modern Catholic Church.

Modern Christianity (1700 AD-Present)

Modern Christianity saw the Enlightenment challenge traditional religious authority, while Vatican II (1962–1965) brought reforms, emphasizing ecumenism and modernization. Global Christianity expanded, with Pentecostalism flourishing.

5.1 The Enlightenment and its effects on religious thought

The Enlightenment (18th century) challenged traditional religious authority, emphasizing reason over revelation. Thinkers like Voltaire and Rousseau questioned Church doctrines, promoting secularism and religious tolerance. This era influenced Christian thought, leading to liberal theology and biblical criticism. The Church faced criticism for its dogmatic stance, prompting internal reforms. The separation of church and state gained momentum, reshaping Christianity’s role in society. While some Christians embraced rationalism, others defended traditional beliefs, leading to theological divides. The Enlightenment’s legacy endures, shaping modern religious discourse and the Church’s adaptation to contemporary values.

5.2 Vatican II and its reforms in the 20th century

The Second Vatican Council (1962–1965) was a pivotal event in modern Christianity, initiated by Pope John XXIII to renew the Catholic Church. Key reforms included the use of vernacular languages in liturgy, emphasizing the role of bishops, and promoting ecumenism. The council addressed social justice and human dignity, encouraging engagement with the modern world. It also redefined the Church’s relationship with other religions, fostering dialogue. Vatican II’s changes, such as the orientation of the altar and increased lay involvement, reshaped worship practices. While these reforms were transformative, they also sparked debates and divisions within the Church. Vatican II remains a cornerstone of 20th-century Christian history, influencing the Church’s ongoing evolution.